This past May, Laurens van Hofslot and Olivia Rice, students from University College Utrecht, participated in the commemorative trip. Their involvement was linked to their participation in the interview project of Stichting Sobibor. For this project, both have interviewed various survivors and descendants of the Holocaust. The main goal of this ongoing project is to document the wartime and life stories for families. As a culmination, Olivia and Laurens joined the commemorative trip to Sobíbor.

This past May, Laurens van Hofslot and Olivia Rice, students from University College Utrecht, participated in the commemorative trip. Their involvement was linked to their participation in the interview project of Stichting Sobibor. For this project, both have interviewed various survivors and descendants of the Holocaust. The main goal of this ongoing project is to document the wartime and life stories for families. As a culmination, Olivia and Laurens joined the commemorative trip to Sobíbor.

Laurens writes that although he is deeply involved with this topic through the interview project, he himself does not have a Jewish background. He was initially worried that this might make him feel like an outsider, but nothing was further from the truth. Olivia and he were warmly welcomed into the group, and this trip provided him with valuable new insights and knowledge. The most significant learning experience, writes Olivia, was not from the different museums or places we visited, but from being part of the group. The group was open, friendly, and always ready for a chat during bus rides and pleasant dinners. These interactions were not merely superficial; Olivia also learned a great deal about various aspects of Jewish culture.

During the trip, we visited many different places. Our journey started in Warsaw, where we arrived by plane. Our first visit was to the Jewish Historical Institute, where we received a fascinating and shocking insight into life in the Warsaw ghetto and how the Jewish resistance was organized during the war. After this visit, we traveled to Lublin, where we stayed at a hotel during the trip. On days 2 and 3, we visited Wlodawa with the group to see two synagogues. These synagogues can be visited but are no longer in use. There, we learned more about the history of the Jewish community in this region. From Wlodawa, we proceeded to Sobíbor camp, where we received a brief explanation of what the camp looked like and how it operated, complete with testimonies from survivors. There was also an opportunity to visit the museum and see the memorial path with the stones.

In accordance with Jewish tradition, we also held a memorial ceremony at the ash mound, where people could name their family members. This moment was very emotional and left a deep impression. It was very powerful to see and hear that, despite everything, these families could be here to honor their relatives, despite the immense suffering inflicted upon their families. Olivia writes how the kind and friendly group made this moment of remembrance in Sobibor camp even more poignant. “I truly realized that day what the impact of the Holocaust really was. It is easy in the academic world to distance yourself from the tragedies and human rights violations you learn about. The commemoration left an impact that ensures I will never do this again.” Laurens also writes that as a student, you can sometimes easily fall into the trap of dealing with Holocaust information in an academic manner, but this commemoration made the stories of the Holocaust tangible for him in a new way. The stark contrast between the location of Sobíbor camp—a seemingly peaceful place in the middle of the forest, where the sun shines, and birds sing—and the atrocities that took place there was jarring.

In accordance with Jewish tradition, we also held a memorial ceremony at the ash mound, where people could name their family members. This moment was very emotional and left a deep impression. It was very powerful to see and hear that, despite everything, these families could be here to honor their relatives, despite the immense suffering inflicted upon their families. Olivia writes how the kind and friendly group made this moment of remembrance in Sobibor camp even more poignant. “I truly realized that day what the impact of the Holocaust really was. It is easy in the academic world to distance yourself from the tragedies and human rights violations you learn about. The commemoration left an impact that ensures I will never do this again.” Laurens also writes that as a student, you can sometimes easily fall into the trap of dealing with Holocaust information in an academic manner, but this commemoration made the stories of the Holocaust tangible for him in a new way. The stark contrast between the location of Sobíbor camp—a seemingly peaceful place in the middle of the forest, where the sun shines, and birds sing—and the atrocities that took place there was jarring.

The most remarkable thing to see and experience was the strength of the group, not only in honoring their relatives but especially in their efforts to add an educational element to the trip. On the third day of the trip, a group of Polish students from Lublin joined us. It was a very valuable addition to our second visit, as we could learn a lot from each other, and the descendants and survivors in our group could share their family stories with this new generation. On the last day of our trip, we returned to Warsaw, this time visiting the Polin Museum. Here, we had the chance to immerse ourselves interactively in the history of the Jewish population in Poland.

Laurens concludes that the entire trip was an emotional but incredibly special and valuable experience. “I think I will never forget this experience, and I came home with a new perspective on both this dark part of our shared history and the world around me. I am very grateful for the opportunity to go on this trip and feel fortunate that Olivia and I could be part of such a close-knit group with different families, generations, and backgrounds where we learned a lot from each other and formed a special connection in a short time!”

This year, the Rozendaal family, with two brothers, three sisters, a granddaughter, and their partners, also joined the commemorative trip. During the memorial ceremony, the eldest brother, Walter, recited the following poem written by his son Bas:

How Can the Sun Shine in Hell?

My expectations pitch dark,

like a looming thundercloud.

What unfolded here,

impossible to imagine, nor comprehend.

A systematic murder machine

operated by flesh and blood.

How could I think that, from my balcony,

I heard the same night sounds as you did then?

Driven in at morning,

never to see the evening.

And now, here I stand with my dear Sanne,

in a bewildering contrast.

No mud, no grim shroud,

but a warm spring sun.

How can a place like this

look like a peaceful nature reserve?

Sobibor, place of doom and survival,

too heavy for me to hear about.

For years it’s echoed in my mind,

drawing personal conclusions.

I see myself a victim,

one of them.

One of the millions

who had to be exterminated.

Not worthy to exist,

not meant to live.

And that’s why I am here,

no longer trapped in those thoughts.

I wish to honor and remember,

I am not dead, I live.

Perhaps this is my tribute,

my breath each day.

My existence, my descendants,

a defiant gesture to the madness.

And that is why the sun may shine here,

why life may go on here too.

Because no budding green leaf on the trees,

no truck dumping gravel,

Can make us forget history,

as long as we are here,

that we are here.

The Sobibor Foundation participated in an International Seminar Tour in Lublin and Region June 16-21, 2024: Unveiling ‘Aktion Reinhardt’: A Multiperspective Exploration. The seminar was organized by Brama Grodzka Gate-Teatr NN in Lublin.

The Sobibor Foundation participated in an International Seminar Tour in Lublin and Region June 16-21, 2024: Unveiling ‘Aktion Reinhardt’: A Multiperspective Exploration. The seminar was organized by Brama Grodzka Gate-Teatr NN in Lublin.

This past May, Laurens van Hofslot and Olivia Rice, students from University College Utrecht, participated in the commemorative trip. Their involvement was linked to their participation in the interview project of Stichting Sobibor. For this project, both have interviewed various survivors and descendants of the Holocaust. The main goal of this ongoing project is to document the wartime and life stories for families. As a culmination, Olivia and Laurens joined the commemorative trip to Sobíbor.

This past May, Laurens van Hofslot and Olivia Rice, students from University College Utrecht, participated in the commemorative trip. Their involvement was linked to their participation in the interview project of Stichting Sobibor. For this project, both have interviewed various survivors and descendants of the Holocaust. The main goal of this ongoing project is to document the wartime and life stories for families. As a culmination, Olivia and Laurens joined the commemorative trip to Sobíbor. In accordance with Jewish tradition, we also held a memorial ceremony at the ash mound, where people could name their family members. This moment was very emotional and left a deep impression. It was very powerful to see and hear that, despite everything, these families could be here to honor their relatives, despite the immense suffering inflicted upon their families. Olivia writes how the kind and friendly group made this moment of remembrance in Sobibor camp even more poignant. “I truly realized that day what the impact of the Holocaust really was. It is easy in the academic world to distance yourself from the tragedies and human rights violations you learn about. The commemoration left an impact that ensures I will never do this again.” Laurens also writes that as a student, you can sometimes easily fall into the trap of dealing with Holocaust information in an academic manner, but this commemoration made the stories of the Holocaust tangible for him in a new way. The stark contrast between the location of Sobíbor camp—a seemingly peaceful place in the middle of the forest, where the sun shines, and birds sing—and the atrocities that took place there was jarring.

In accordance with Jewish tradition, we also held a memorial ceremony at the ash mound, where people could name their family members. This moment was very emotional and left a deep impression. It was very powerful to see and hear that, despite everything, these families could be here to honor their relatives, despite the immense suffering inflicted upon their families. Olivia writes how the kind and friendly group made this moment of remembrance in Sobibor camp even more poignant. “I truly realized that day what the impact of the Holocaust really was. It is easy in the academic world to distance yourself from the tragedies and human rights violations you learn about. The commemoration left an impact that ensures I will never do this again.” Laurens also writes that as a student, you can sometimes easily fall into the trap of dealing with Holocaust information in an academic manner, but this commemoration made the stories of the Holocaust tangible for him in a new way. The stark contrast between the location of Sobíbor camp—a seemingly peaceful place in the middle of the forest, where the sun shines, and birds sing—and the atrocities that took place there was jarring.

And then ‘Sjiwwe for Sobibor’; a theatre project about the 19 trains that went to Sobibor between March and July 1943. ‘Theater Roestvrij’ created a beautiful, moving performance about life in Westerbork before departure and on the train. This production was a collaboration with ‘Theater Na de Dam’ (‘Theatre after the Dam‘), Westerbork Memorial, and the Sobibor Foundation.

And then ‘Sjiwwe for Sobibor’; a theatre project about the 19 trains that went to Sobibor between March and July 1943. ‘Theater Roestvrij’ created a beautiful, moving performance about life in Westerbork before departure and on the train. This production was a collaboration with ‘Theater Na de Dam’ (‘Theatre after the Dam‘), Westerbork Memorial, and the Sobibor Foundation.

On

On

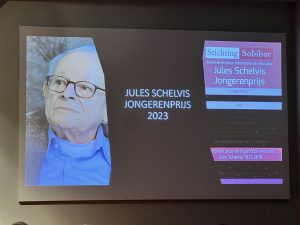

The Sobibor Foundation is proud to announce that the Jules Schelvis Youth Prize 2023 has been awarded to Oscar Visser. His paper, “

The Sobibor Foundation is proud to announce that the Jules Schelvis Youth Prize 2023 has been awarded to Oscar Visser. His paper, “

The Sobibor Foundation established this prize in 2020 for young people, who in a special way bring attention to the former Nazi extermination camp Sobibor and feel involved in contributing to the lasting memory of Sobibor. The Jules Schelvis Youth Prize consists of a certificate and a sum of €250.

The Sobibor Foundation established this prize in 2020 for young people, who in a special way bring attention to the former Nazi extermination camp Sobibor and feel involved in contributing to the lasting memory of Sobibor. The Jules Schelvis Youth Prize consists of a certificate and a sum of €250.